| Love to Work the Land? Meet Today's Farmers for Inspiration

Advice and stories from the folks who grow our food | | Love to work the land? Then you have something in common with today’s farmer. Here are stories, inspirations, and little lessons from folks who grow our food!

Farmers in the U.S. and Canada are diversifying. Their reasons for this range from generating additional income to helping the community to just plain survival. All have one thing in common: They truly love working the land. |

| | Family farms make up 97.1% of farms in America and many of the farmers are creative entrepreneurs who must adjust to an ever-changing market to stay in business. Today, we salute five different farmers who grow our food, recognizing both the younger farmers coming on and the older folks who’ve been feeding us during their lifetimes. |  | | Daryll Breau of Vermont’s Ayers Brook Goat Dairy. Hanging out with a nubian kid goat! | AYERS BROOK GOAT DAIRY

RANDOLPH, VERMONT

Farmers at Ayers Brook Goat Dairy have learned the hard way to goat-proof everything—light switches, doorknobs, the grain auger!

“Goats are curious by nature. They can’t resist the opportunity to fiddle with something. If you look away for 5 seconds, you will have a cleanup project on your hands that will consume your entire afternoon,” says owner Miles Hooper.

A herd of 1,000 does produces milk for Vermont Creamery and a local producer of goat’s milk caramel sauce, among other customers. “It’s a marginal business. A lot of things have to go right for you to get paid,” notes Hooper. Producing high-quality milk is a priority. “Our contribution to the industry is not the amount of milk that we put in the bulk tank, but the genetic work we do to create heathier, more efficient animals,” Hooper explains. “The more protein—particularly casein—that we have in our goat’s milk, the better the conversion factor from pounds of milk to cheese.”

With a healthier profit margin, the farmers preserve both their livelihood and the environment. Recently, Hooper purchased a piece of land slated for development and preserved it for agriculture through a conservation easement with the Vermont Land Trust. In 2014, he added solar panels to a 14,000-square-foot barn, allowing the 266-acre farm to be run completely on solar electricity.

Years ago, Hooper visited goat farmers in rural France who somehow found time for an unrushed midday meal. Living by this example, Hooper intends to show his children that farming doesn’t necessarily mean nonstop labor: “We are trying to keep the farm fun and lighthearted enough that they might actually be inclined to take it on.” |  | | The Baldwin Family and their outstanding gourmet Papa Baldy’s Popcorn. | BALDWIN FARMS

MCPHERSON, KANSAS

Will it pop? That question gave the owners of Baldwin Farms sleepless nights just before their first harvest of popcorn in 2017. “We were very nervous that we would harvest it at the wrong moisture level,” recalls Cindy Baldwin. When an ear of corn was pulled off the stalk, put into a paper bag, and placed in a microwave oven, nothing popped—but the house filled with smoke from the still damp, overheated cob.The waiting game began as the kernels dried a few more days in the field.

During the next test, cobs popped in the microwave, in a stovetop pot, and in an air popper. “We all did a high five—and then we ate it,” smiles Cindy. With that, Cindy, husband Dwight, son Adam, and Adam’s wife Kim became the niche marketers of Papa Baldy’s Popcorn.

For four decades, wheat, field corn, and soybeans have been the Baldwins’ only crops, as the farm increased to several thousand acres. Then crop prices began to fall. “When commodity prices go down, if you have more acres, you have a tendency to lose more money,” Dwight notes.

After a meeting with popcorn breeders, the family decided to try ‘Jumbo Mushroom’ popcorn and devoted a 5-acre field to it. Dwight took on sales, offering free samples at countless sales venues.

Today, the Baldwins have a diverse mix of retail customers. Yields aren’t nearly as high as they are for field corn, but popcorn’s selling price is much higher.

The farm allocated an additional 3 acres to popcorn in 2018, and the family is experimenting with poppable sorghum. “We had a good first year, and we are hoping for a good second year,” says Dwight. “We’re just going to see where this goes.” |  | | Farmer Dwight Baldwin (known as Papa by his grandchildren) of the Baldwin family-owned farm in Kansas. | SANTA CRUZ FARM

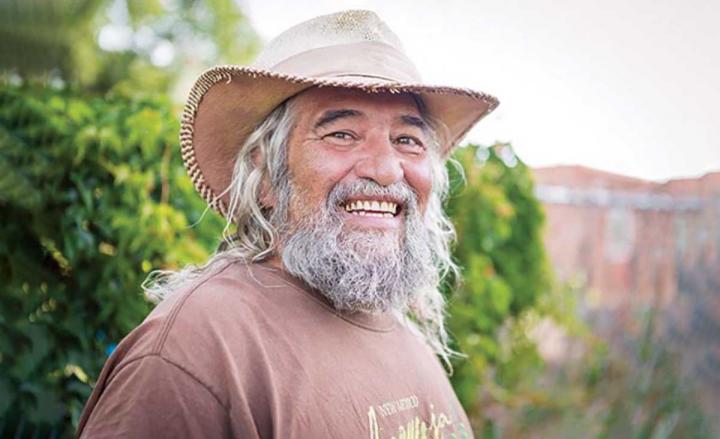

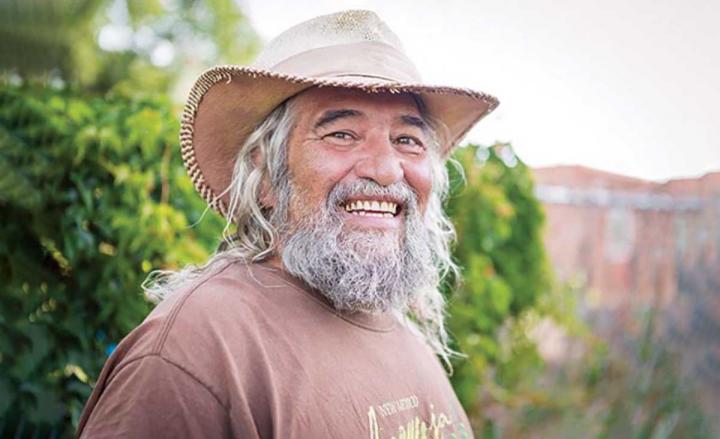

SANTA CRUZ, NEW MEXICO

At Santa Cruz Farm, 72 varieties of organic produce grow on just 3½ acres. “It’s a beautiful, small, diverse farm. I farm the same land that my ancestors farmed 400 years ago, basically using the same techniques,” says owner Don Bustos.

As a child, Bustos could often be found behind a mule, plowing for his grandfather on the family’s farm. Over time, the property became overgrown. In the 1970s, Bustos began converting his farm from 100 acres of row crops to 3.5 acres of year-round organic production with more than 70 varieties of fruits and vegetables. In 2015 he was the recipient of one of five James Beard Foundation Leadership Awards, which recognize “who influence how, why and what we eat.”

The tiny farm is a four-man operation: Bustos and two employees work the land, and his nephew handles sales at six local farmers’ markets, all within 25 miles. “We have a little bit of wholesale here and there, but direct sales seem to be more profitable for us,” reports Bustos. Customers know that Santa Cruz Farm is the only place to find locally grown blackberries and strawberries—and cucumbers off-season.

Success stems from tried-and-true practices paired with cautious, lowcost innovations. “Being a small farm, we are very risk-averse,” notes Bustos. “But small investments add up to big profits, if done correctly.” High tunnels were added to extend the growing season. Switching to a root-zone heating system saved money; the heating bill for the small greenhouse, once $750 a month, is now just pennies a day. “This is what allows us to grow greens in the middle of the winter,” says Bustos. He is passionate about training beginning farmers: “My philosophy is not to grow the farm, but to grow more people to farm. It’s not about just one person. It’s about the whole community flourishing.” His advice: Go all in. “If you approach farming as a full-time job, you will be successful. But if you try to farm and do something else on the side, then you marginalize your chances.” |  | | Don Bustos farms in the village of Santa Cruz in northern New Mexico on land his family has owned for more than three centuries. | FRESH FUTURE FARM

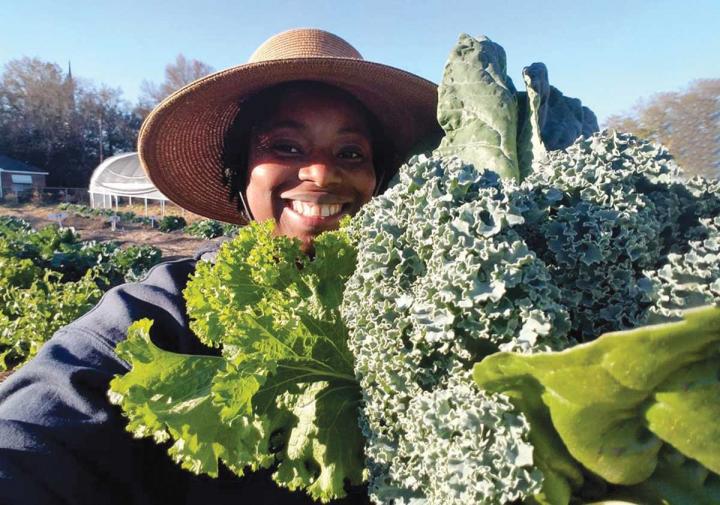

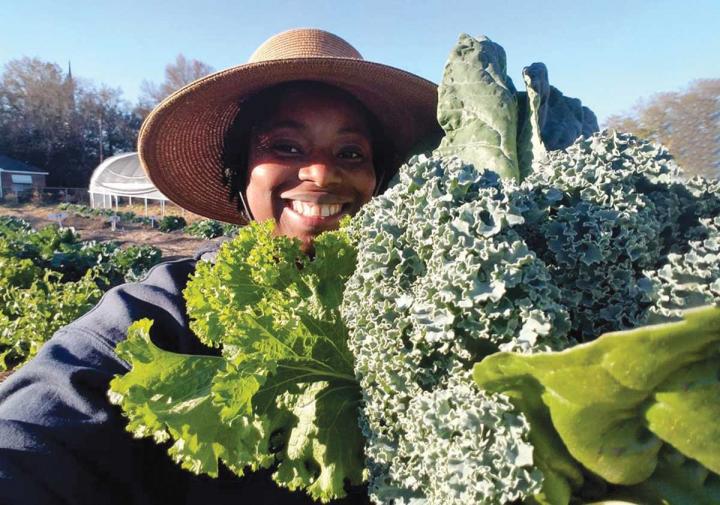

NORTH CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA

When Germaine Jenkins and her children lived in an apartment building, she promised them that they’d have a garden someday. When she moved to the Low Country to attend culinary school and became a homeowner, she kept her word.

The first step was digging up and giving away the azaleas in the front yard. In their place, she planted blueberries, orange trees, and sweet potatoes, and she kept chickens in the back for egg production and manure. Curious kids riding by on bikes would ask, “Is this a farm?”

The question was prescient. Jenkins soon convinced North Charleston city officials to lease her a .81-acre vacant lot. She marked its boundaries with fruit trees and, over time, it became Fresh Future Farm. “Slowly, we built up the farm,” she recalls.

Today, the farm is the source of an astounding variety of the freshest, most nutritious produce that some locals have ever had. Fresh eggs come from the farm’s chickens; compost, from garden waste; mulch, from cardboard boxes donated by a local business; the store building, from the owner of a rental car company who no longer needed it. The five employees who manage the store and field are paid through donations and store revenue. Volunteers, ages 15 to 73, prepare the fields, plant, and harvest. “Everyone who works here either volunteered, interned, or shopped here for months before they got the job,” reports Jenkins.

Families, school kids, and tourists visit the farm and learn about its sustainable ways, like capturing rainwater and keeping bees for pollination. Jenkins plans an online class on “agricultural entrepreneurship”: “It will show the basics, so that the next person who does this skips all of the mistakes that I made. We don’t just want to grow food. We want to grow gardeners! |  | | At Fresh Future Farm, Germaine Jenkins cultivates healthy eating for underserved communities—and grows gardeners! | THE HOUWELING GROUP

DELTA, BRITISH COLUMBIA

Gone are the days when flakelike tomato seeds are planted in the nesting cavities of an egg carton—at least for Ruben Houweling who is the propagation manager for The Houweling Group, a tomato grower in British Columbia which specializes in one business—greenhouse tomatoes.

He has fine-tuned a process that takes Dutch seeds to 20-inch transplants for commercial growers to buy in 6 weeks. The Houweling Group, run by Ruben’s uncle Casey Houweling, produces seedling tomato plants for about half of the commercial greenhouses on the western coast of the U.S. and Canada! These plants produce the tomatoes that are sold in many grocery stores. “To plant a seed and plant a crop is to believe in tomorrow,” says Ruben.

Each seed is deposited into a plug to settle in for 2 weeks. Then, workers graft a fruiting seedling to a rootstock seedling. This new plant goes into a humidity chamber for a week for the graft to fuse. The grafted seedling is then planted into a 4-inch cube of rock wool, an inert substrate. One week later, these cubes are placed in a greenhouse nursery to be nurtured by frequent doses of fertilized water. When the first flowers appear, the transplants are shipped to the growers.

Despite the assistance of state-of- the-art lighting and irrigation, the greenhouse is in tune with each season’s climatic variations. Says Houweling: “Especially through the fall, winter, and spring, we are aware of available light and the angle of the Sun. We still need to harvest as much free solar energy as possible.”

Houweling reports that they plan to expand the seedling service in the near future, another example of the current high-density trend in agriculture to produce more on less land, while protecting plants from the harshest elements of weather. |  | | Proprietor Casey Houweling transformed his father’s farm into one of the top tomato greenhouse growers in the world. | NATIONAL FARMER’S DAY

Did you know that October 12 is National Farmer’s Day? This is an opportunity to honor hardworking farmers throughout American history. Only 2% of us feed and sustain the rest of us. Let’s show farmers some love! Learn more. | | | | You received this email because you signed for updates from The Old Farmer's Almanac.

If you do not wish to receive our regular e-mail newsletter in the future,

please click here to manage preferences.

*Please do not reply to this e-mail*

© 2021 Yankee Publishing Inc. An Employee-Owned Company

1121 Main Street | P.O. Box 520 | Dublin, NH 03444

Contact Us

View web version | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment